English as a CFG

First published on: 2022-12-20

As a computer science student, I have spent a fair amount of time studying context free grammars (CFGs) in the context of compilers and automata. They are a powerful tool, useful for defining parsers, but something I'm sure alot of other computer science students won't know about is their use in linguistics too.

The word syntax to most computer science students will immediately bring to mind semi-colons, curly braces, and indentation rules, but it is also used in linguistics to talk about a similar concept - how we form sentences from words.

You may not think about it when you speak, but the order of your words is obviously very important. To say "John hit the dog" and "The dog hit John" means very different things, and to say "hit John dog the" means absolutely nothing.

Notation

Let's start by defining some notation to simplify our CFGs. The Kleene star, as you probably know, allows us to have as many copies of a variable as we'd like, including zero. We will write X* for this, as we know we could simulate it in a standard CFG as follows:

A -> XA | ε ≡ X -> A*

In addition, we will use brackets to show an optional element, which we could simulate in a standard CFG as:

A -> X | ε ≡ A -> (X)

Building The CFG

It is easiest to think about this from bottom up: We'll start by considering one of the simplest components of a sentence, an adjectival phrase. An adjective can be modified by an adverb, such as in the adjective phrase "really blue". This gives us the following rule:

AdjP -> (AdvP*) Adj

Notice that we put AdvP (adverbial phrase) instead of Adv (adverb). This is because we can modify our adverbs with another adverb, like when we say "very quickly". This gives us the following recursive definition for an adverbial phrase:

AdvP -> (AdvP*) Adv

The final easy phrase to define will be the prepositional phrase. This one consists of just a preposition, followed by a noun phrase, such as in the phrases: "in the blue house", "with the sharp knife", "under the very blue table with black legs"

PP -> P NP

Now we can consider something a bit more complicated, like a noun phrase. At its most basic, a noun phrase must have a noun.

NP -> N

In English, we put adjectives before the noun, and we can have as few or as many as we'd like, so we can add in our AdjP:

NP -> (AdjP*) N

This structure allows for noun phrases such as "big red dog" and "light green book." Notice the subtle difference between these two, which is that in the first, both "big" and "red" are modifying the noun dog, whereas in the second, "light" is part of the adjective phrase because it modifies "green".

We also use determiners (words such as "the", "a", "my", "that") at the start of a noun phrase, but only one:

NP -> (Det) (AdjP*) N

We can also modify a noun with a prepositional phrase, such as in "the folder on the desk"

NP -> (Det) (AdjP*) N (PP*)

And finally, we can add relative clauses, which we'll define later.

NP -> (Det) (AdjP*) N (PP*) (CP*)

Now we should talk about conjunctions for a bit: "The dog and the man" is a valid noun phrase, and "The man who eats alot and who has nice hair" is also a valid noun phrase.

The way conjuctions work is they can take two of the same type of phrase and join them into one, but they cannot take two different types of phrase: "*The dog and with brown fur". We could show this by defining rules such as NP -> ... | NP conj NP, PP -> ... | PP conj PP, but for the sake of convenience we will simply say

XP -> XP conj XP

where X can be any type of phrase.

Now moving upwards towards the root of the sentence, we have verb phrases. You may remember from English class in school that a sentence consists of a subject and a predicate, and verb phrases here will represent that predicate.

VP -> V

Obviously verbs can take adverbs, but the interesting part is they can go on either side of the verb: "He ran quickly", "He quickly ran"

VP -> (AdvP*) V (AdvP*)

We can also modify verbs with prepositional phrases, as in "He ran towards the bridge", and note that the adverb can go on either side of this too: "He ran quickly towards the bridge", "He ran towards the bridge quickly"

VP -> (AdvP*) V (AdvP*) (PP*) (AdvP*)

And finally we need to consider the transitivity of the verb, which means how many arguments it takes. For example, we can say "I sleep", because it is an intransitive verb, but not "I need", as it is a transitive verb that requires a direct object.

VP -> (AdvP*) V (NP) (NP) (AdvP*) (PP*) (AdvP*)

Arguments to a verb are noun phrases, and you may have noticed that I added two NPs and this is because of ditransitive verbs, which take two objects, as in "I gave you the book."

So, our overall sentence will consist of a noun phrase as the subject, and a verb phrase as the predicate, giving us:

TP -> NP VP

We are missing one element, which is auxilliary verbs, used to mark some tenses in English such as the future ("I will eat"). This is why this type of phrase is called a TP, which stands for tense phrase.

TP -> NP (T) VP

It is worth noting that our XP -> XP conj XP construction applies here, allowing us to form compound sentences such as "I ate the rice and I went to the store"

We are just left with clauses, which are simply a sentence with an optional relativiser(a word like "that" or "which")

CP -> (C) TP

The CFG

The whole set of rules we have so far is:

CP -> (C) TP

TP -> NP (T) VP

VP -> (AdvP*) V (NP) (NP) (AdvP*) (PP*) (AdvP*)

NP -> (Det) (AdjP*) N (PP*) (CP*)

AdvP -> (AdvP*) Adv

AdjP -> (AdvP*) Adj

PP -> P NP

XP -> XP conj XP

Let's take a look at some sentences and check that they fit our rules:

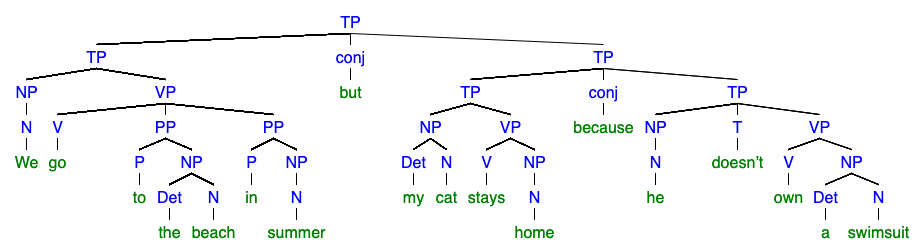

"We go to the beach in summer, but my cat stays home because he doesn’t own a swimsuit."

We can deconstruct this into the following, which if you look at each phrase, abides by the rules.

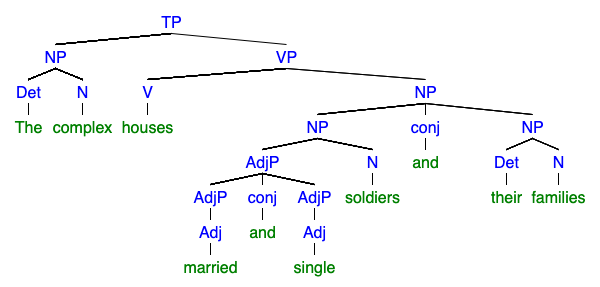

We can also try and deconstruct some "garden path" sentences, which is a linguistic term for a sentence that takes a few passes to properly understand.

"The complex houses married and single soldiers and their families."

Seeing the parse tree helps make it clear that "houses" and "complex" are not as closely linked as they appear when you read the sentence for the first time.

Conclusion

Our CFG is obviously not exhaustive, as questions and commands have different structures, and we didn't create individual rules for different verb transitivities (exercises for the reader!). But I still found it pretty interesting to see that CFGs are able to capture natural language as well as regular and programming languages, and hope you learned something while reading.

If you'd like to read more on this topic, I'd highly recommend Andrew Carnie's Syntax: A Generative Introduction.